On the recommendation of my tutor I recently watched Metropolis (1927) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) as a part of my research. You might question what relevance silent films made over fifty years before the era of cyberpunk have to my studies – indeed I certainly did at first – however on closer inspection both feature elements which may well have helped form the foundations on which the genre is built.

I’ll warn you right now if you haven’t seen either expect remorseless plot spoilers…

Still with me? Considering Fritz Lang’s Metropolis first, a film it’s fair to say is among history’s most famous sci-fi and subject to a string of restorations including the recent re-release featuring lost footage. To those unfamiliar with the movie, the story is centred around a titular futuristic metropolis where the lives of the wealthy are supported by the slavish efforts of a subterranean worker class. Naturally tensions and resentment between the two groups are constantly high with the threat of chaos erupting at any moment, something held back by promises of a mediator’s arrival by the worker’s saintly prophet Maria. Unfortunately the metropolis’ tyrannical dictator Joh Fredersen – fearing an imminent uprising – takes matters into his own hands, devising a scheme to forcibly inspire a rebellion which he can quell: To kidnap Maria and replace her with an evil robot replica which will stir the workers up into violence.

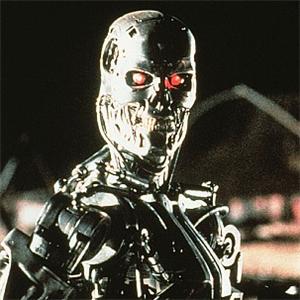

Even if you haven’t seen the film you will certainly have encountered the robot’s iconic image somewhere, a visual quote appearing throughout countless textbooks, documentaries and consequent inspirations – just look at C3PO in Star Wars. It’s likely one of cinema’s earliest aesthetic uses of a robot and while it’s been a huge influence on science fiction generally I’d still argue there are connections to the cyborg concept.

This connection comes from the manner in which the robot is transformed from mechanical construct to a being seemingly of flesh and blood, taking on Maria’s appearance to uncanny effect. In a sense it seems like a reverse cyborg, the machine taking on human characteristics rather than the reverse: a machine being humanised rather than a person being dehumanised by the machine. It’s a concept the Terminator films are built on, while more specifically in relation to my work there also appear to be echoes of the idea in Blade Runner’s Replicants.

Strangely, the film does unwittingly stumble directly onto the cyborg in a throwaway moment. While talking with Fredersen, the inventor ‘Rotwang’ who created the robot dramatically raises a gloved hand and says “Isn’t it worth the loss of a hand to have created the workers of the future – – the machine men?” This is all the explanation we get as to the nature of this artificial (and seemingly movable) hand, but taken literally this would make Rotwang one of cinema’s earliest cyborgs.

I’ve mentioned Blade Runner once already, but again traces of possible inspiration are present in other areas of the film, namely its grandiose sets. A towering cityscape of burgeoning skyscrapers, glittering lights and transport – themselves apparently inspired at the time by Manhattan’s skyline. Fantastic but simultaneously disturbing thanks to their uncanny resemblance to our modern equivalent. Even more unsettling are the film’s open shots of the machines beneath the city, their presence emphasising their prominence in the narrative from the very start while even the workers initially appear machine-like in their motions. It’s in these areas that the strongest links to cyberpunk become apparent, namely the driving idea of high technology, low humanity. We see a machine becoming human while we simultaneously see workers dehumanised by machines.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is of wholly different and less obvious relevance to my subject matter and I’ll admit it took two viewings and a commentary for me to truly grasp it, however at its heart is something I could swear I’ve seen in the vast majority of cyberpunk narratives – the fear of uncertainty.

From a visual standpoint the film is already distinct, infusing it’s backgrounds and sets with the warped sensibilities of German expressionism, while coloured filters and use of heavy shadowing creates a surreal atmosphere, establishing a sense of unease in the viewer from the get go. We are initially presented with a flashback story from Francis: a man we take to be hero of the piece, telling the story of his friend Alan’s murder and his ensuing search for the killer. This portion of the narrative (which takes up the majority of the runtime) is an engaging but ultimately predictable affair following the then popular format of a detective story, with a streak of horror running alongside it.

The title villain Dr. Caligari is a fairly typical ‘mad scientist’ archetype, comparable to Rotwang in appearance and behaviour, while his Somnambulist freak show ‘Cesare’ – manipulated into murderous acts at his whim – is reminiscent of classic movie horrors such as Nosferatu and Frankenstein’s monster. A cat and mouse game ensues: Francis is briefly put off the trail before gradually following clues, finally proving the doctors madness and having him institutionalised. A satisfying, but largely conventional narrative is concluded and the viewer relaxes, prematurely as it turns out.

Returning to the present from which the flashback has been told we learn that Francis is in fact himself a patient in a mental institution, the story he’s just told nothing more than a delusion which he has populated with fellow inmates and most notably the asylum director: Dr. Caligari, in reality of a conversely benevolent personality and intentions. Everything that came before is thrown into a new light as we discover the unreliability of our narrator, the warped angles and strange colours of the flashback presumably the hallmarks of a deranged mind, playing on a subjectivity in filmmaking which was largely unheard of at the time.

To my mind at least this twist ending taps into a much deeper horror than that of any somnambulist murderer or mad doctor, it taps into our fundamental fear of the unknown – the idea that what we know is lie and that uncertainty lies beneath the surface. I’d argue that this fear of the unknown is a core component in many cyberpunk films: Dark City (1998) and the reveal of its titular location as a giant Petri dish, The Matrix (1999) and it’s treatment of surface reality or again, how Blade Runner brings Deckard’s humanity into question. This deconstruction of established settings and knowledge has become a staple in much of cyberpunk cinema, and while it would be presumptuous to suggest The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is the root influence, it’s likely it had some part to play, however indirectly.

It just goes to show, Cyberpunk may be relatively recent but its themes and ideas were already being developed with the arrival of the modernism – something which both films emphasise.

Posted by Ozy

Posted by Ozy