It occurs to me that I’ve made mention of Frank Miller’s Sin City a few times now in relation to my concept work without including a specific write up about it on this blog. Having read the first instalment The Hard Goodbye (1991) and included an entry in my folder I figured one was in order here.

Prior to reading, I was already something of a Miller enthusiast thanks to The Dark Knight Returns (1986) but had little knowledge of Sin City beyond a few glimpsed pages and the Robert Rodriguez movie adaption. His art here remains identifiable largely through the grizzled protagonist ‘Marv’ resembling TDKR’s aging Batman, poses featuring his billowing trench coat recalling the latter’s cape. At the same time though the approach remains quite different. Style and technique here are minimal, eschewing colour in favour of stark black and white compositions; an approach which sets the graphic apart from the author’s preceding work.

The titular setting of Sin City is probably most notable for never specifying its location or exact period. References are made to everything from war torn Baghdad to 1950’s fashion trends. While this is only my take on the reason behind this ambiguity, I feel perhaps the intention was to free the story from restrictions of an exact backdrop, allowing the purest homage possible to the collective film noir and pulp fiction of the 20th century; a mish-mash of cherry picked influences you might say.

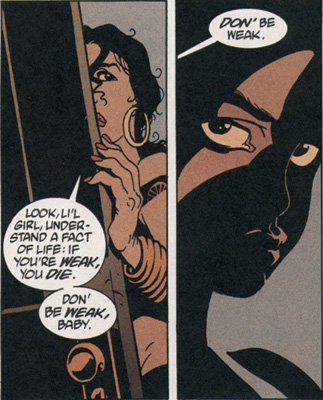

Though the influences may be worn on its sleeves, the story quickly sets itself apart from a plethora of similar works with some distinctly unconventional elements. Take the love interest Goldie for example – rather than being developed through a gradual romance she is introduced at the start in an opening sex scene before being abruptly murdered; a swift entrance and departure certainly but one which provides a genuinely compelling motive for Marv’s ensuing revenge. Elsewhere I think it’s fair to say most hardboiled detectives wouldn’t be caught dead visiting their mother’s house to collect a gun and yet it’s a moment which pushes past the established clichés and injects a sense of reality into the melodrama. The formula is pushed and warped in unexpected ways but remains uncompromised, for all its idiosyncrasy Sin City keeps a foot firmly in its subject genre.

Marv himself makes for an unlikely detective figure too: self described as dim witted and ugly he never hesitates in resorting to violence while an unspecified mental condition causes him to imagine things or become “confused”. He’s an anti-hero certainly but frequently appears alarmingly monstrous even by this measure. Besides inflicting injury and torture upon his enemies comparable to even the story’s worst villains, the inhuman amount of damage he takes from guns, cars and weapons throughout furthers the image of him being a sort of abomination.

I formerly mentioned how the opening murder provides a genuine motive for Marv’s actions later but at the same time the constant introspective narration seems to challenge this idea. While he does have a personal stake in avenging Goldie there’s something oddly wanton to the glee Marv takes in the carnage, as he puts it to his parole officer “This is big and I’m right in the middle of it and there’s no place I’d rather be.” Perhaps in this sense the character is intended as a comment upon the audiences’ insatiable thirst for violence and tales of revenge, these moments of excess hinting at a metaphysical purpose for his existence and the carnage: to entertain the readership’s own dark desires.

Alternatively, I may be over thinking what is in essence a guilty pleasure. There’s a near continuous deluge of fighting, sex, murder, prostitutes, torture and cannibalism across the pages with few punches being pulled in the depiction of brutality. The violence isn’t mindless but nor is it particularly subtle either. Were I asked to consider which it has more of between style and substance, I wouldn’t hesitate to say style.

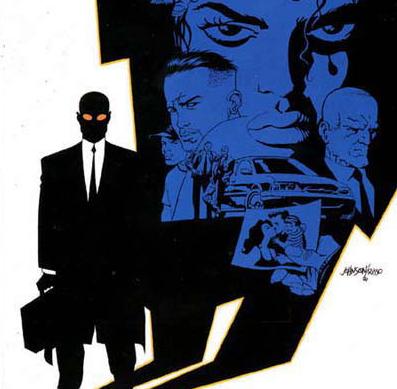

Fortunately it is in style that Sin City really excels. At times it can seem deceptively minimal for a graphic novel, characters and frames often lacking the firm outlines so commonly associated with comic books, but these economical black and white inks are ultimately all the more impressive for so clearly suggesting characters and scenery with so little. Patterns of light and shadow result in truly striking poses and expressions while bringing the stark contrasts of classic era noir to mind. More outlandish touches often add a surreal element to the atmosphere too, something which seems all the more fitting in light of the protagonist’s deranged mind state. The classic noir silhouette is often inversed presenting light ghostly figures against a dark background as opposed to visa-versa, while the plasters on Marv’s battered face are occasionally highlighted as well covering him in tiny neon crucifixes – perhaps in reference of having the Cardinal Roark as a villain or alternatively portraying Marv as some twisted form of Martyr for Goldie; punishing the wicked only to take the fall for everything at the cost of his life.

Given the smaller page size, emphasis on mood and large amount of action Miller fittingly opts for less panels of a larger size, allowing the artwork to take centre stage and really shine as a result. Occasionally the layouts can seem quite bizarre in this regard with a drawing only taking up a small portion of the page, but I suppose this only serves to draw focus on the moments in question, setting them apart from other sequences and giving them breathing room. Special mention should also be made of text such as onomatopoeias, with sound effects and exclamations often being a seamless and integral part of the art – the famous “BLAM! BLAM! BLAM!” page being a strong example of this.

Looking at the similarities Sin City bears to other works, beyond the obvious film noir inspiration I can see elements of Eisner’s The Spirit in the art – which Miller coincidentally directed the unfortunate film adaption of – while it doesn’t seem a stretch to suggest that more recent works such as 100 Bullets may have taken note of the economical style and technique used here too. If I were to take one thing from the book it would be that sometimes less is more, the suggestion of an object rather than a clear cut depiction being enough in itself, while often being far more interesting and atmospheric. Detail and realistic depiction isn’t everything.

Posted by Ozy

Posted by Ozy