It’s funny; I’ve been watching cartoons populated by his characters since carefree childhood days and I’ve been at least aware of his historic contribution to comics for many years now, but up until a few days ago I knew precious little about the man himself and exactly how big a contribution it was.

Jack Kirby (born Jacob Kurtzberg) is a name almost invariably associated with brilliance in the medium. With many of the characters he helped create now deeply embedded in popular western culture few artists or authors can claim such an enormous legacy. Referring to Masters of American Comics (2005), Glen David Gold puts it into perspective in his insightful essay ‘Lo, From the Demon Shall Come – the Public Dreamer‘:

‘The superhero gig is a harsh one for creators – it seems that each person (or team) is allotted just one character that outlives them. Bob Kane and his many assistants got Batman – just Batman – and Siegel and Shuster got Superman. But Kirby? Captain America, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, Hulk, Sandman, Thor, New Gods, Forever People, Mister Miracle, each of them with supporting casts that could carry their own comic books. And what a variety of genres he contributed to (or pioneered): superheroes, westerns, romance, kid gangs, science fiction, adventure, crime, horror, Classics Illustrated, animation, creator-owned independents, autobiography, and even, when things got slow in the 1950’s, the bizarre ‘Strange World of Your Dreams’ and ‘Win a Prize’ comics.’

(Gold, 2005, p261)

These superheroes have not only seen decades worth of follow ups and spin off’s in their own medium, but cartoons, toys and recently film adaptions aswell. Thus, it seems rather fitting that I base this write-up around my visit to a Kirby inspired exhibition.

Taking a day trip to Orbital Comics I found the exhibit to be small but densely packed with a variety of work in tribute; all interesting, colourful and intriguing with a host of familiar faces shown in some unexpected ways. Still, while there was plenty to enjoy at face value, reading about Kirby’s career afterwards gave me valuable insight into the inspiration behind these homages. Considering his artistic development during the longterm collaboration with Marvel and Stan Lee (1958-1970), Gold writes:

‘As Kirby’s imagination exploded, so did the storytelling. The “camera” moved closer, the characters’ expressions grew more vivid, the machines more complex, the violence more brutal. His forms became more geometric and stylised. Every surface, including human skin, gleamed like chrome. Every starscape exploded with mysterious dots and “Kirby Krackle.” Fight scenes, which had already looked sweaty, and punches, which had already resonated with the crack of bone on bone, found extra volume; they went up to eleven. When pencil wouldn’t cut it, Kirby got out the scissors and paste and made collages.’

(Gold, 2005, p261)

The energetic qualities described were present in spades for much of the art there with bright colours and packed compositions dominating the space, a particularly obvious acknowledgment to the ‘Kirby Krackle’ being Vlad Quigley’s series of Kirby Kosmic Kollage prints; psychedelic dreamscapes capturing much of the classic Kirby style while also curiously resembling something Moebius/Jean Giraud might have drawn – a favourable comparison to my mind and strangely fitting given his own collaboration with Stan Lee in the 80’s.

Oddly enough another piece I felt strongly resonated with this aesthetic – The Neon City (below) – was actually made by my tutor Mark Wigan; painted in his own signature style but capturing the often dense imagery of Kirby’s own landscapes along with its sense of scale and vibrancy.

(Please note that the exhibition images are ‘borrowed’ from elsewhere as judging by the disapproving look my camera got photography was disallowed at the exhibit ).

Along these lines much of the work is seemingly in pure celebration of the late master’s accomplishments, but at the same time much of it adopted a considerably darker tone perhaps in exploration of the subdued discord which ran throughout his career. Stan Lee wrote of Kirby in his autobiography “There have always been artists who concentrate more on producing impressive illustrations than on visually telling a story in a clear, compelling way. Jack wasn’t one of them. As amazing as his artwork was, he also depicted a story that you could almost follow without reading the words.” which might be seen as unfettered praise, however Gold’s thoughts suggest something of an implication:

‘there is very little pure Kirby in the world. Mostly, he penciled, meaning he was at the mercy of inkers’ interpretations. And Kirby is famous mostly as co-creator. He worked with Joe Simon first, and then with Stan Lee, who wrote (…) some of Kirby’s most memorable stories at Marvel comics. On his own, Kirby’s dialogue betrayed a tin ear, a hipster techno-pastiche something like Thomas Pynchon’s, groaning with the cargo-ship-tonnage conveying of theme.’

(Gold, 2005, p261)

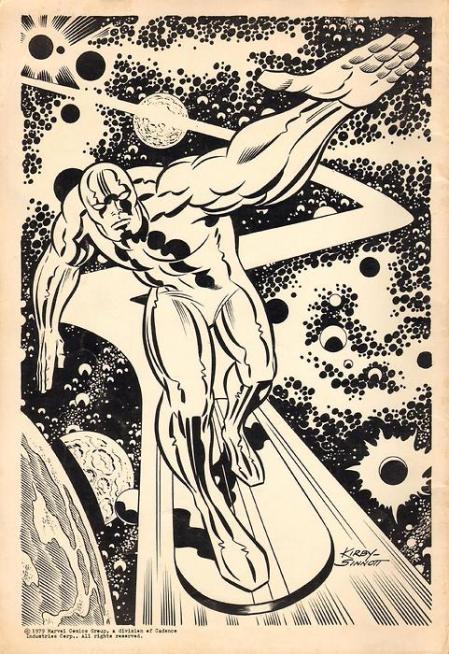

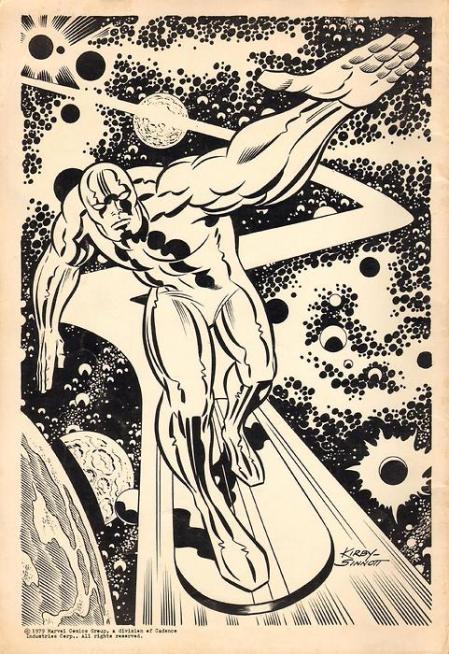

Perhaps it was this reliance upon collaboration in the creation of his most famous works that caused Jack Kirby to feel underappreciated and leave Marvel in the late 1960’s. Only vague details are known as to the exact nature of the disagreement and it wouldn’t be the first (or last time) he changed employer, but a particularly telling incident occurred when Lee launched a standalone Silver Surfer comic (One of the characters they co-created no less) without Kirby’s involvement:

‘The 1968 ‘Silver Surfer’ comic book – made without Kirby’s involvement – failed. In 1970, Lee (somewhat insultingly) called Kirby to do a fill-in issue. It ended up being the last, or almost last, work Jack did for Marvel before leaving. And for eighteen of its twenty pages, it’s uninspired. Fight, fight, fight. Misunderstandings lead to more fights. But then on page nineteen, depriving readers and management of the final confrontation they wanted to see, the Surfer streaks away. It’s hard not to read this as driven by Kirby taking his toys and declaring ownership one last time of a defeated, embittered Silver Surfer.’

(Gold, 2005, p267)

The final page of the aforementioned issue (above) is almost certainly Kirby projecting his own frustration onto the Surfer in a surprisingly personal move; an artist fed up with being constrained and misused. It foreshadows his imminent departure back to DC (then known as National) Comics but also suggests an unexpectedly emotional involvement with his creations rather than the business like attitude some have suggested.

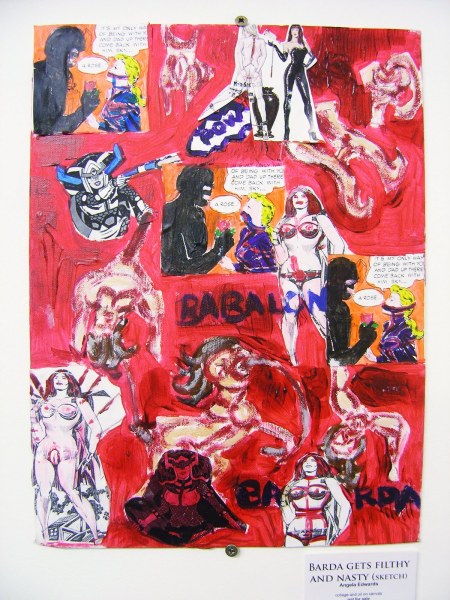

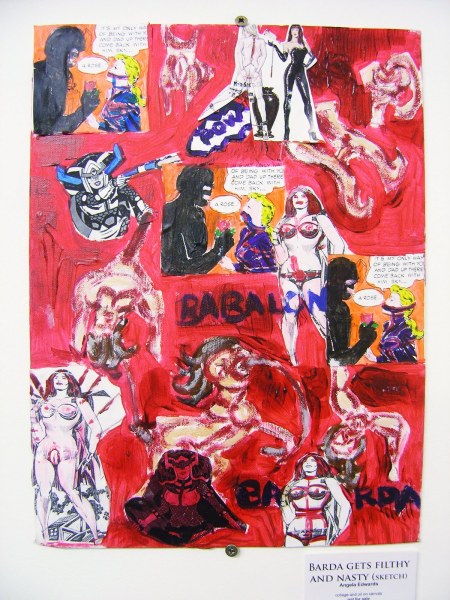

It’s a frustration which was blatantly emphasised in exhibit pieces such as the Feroze Alam’s Kirby-Hulk want Stan Lee Dead (the title says it all really) and Angela Edwards’ violent mutilations of classic Kirby imagery such as Barda Gets Filthy and Nasty (below). These are tributes loaded with as much resentment as they are appreciation.

Following his departure from Marvel Kirby’s work pushed into experimental territory seemingly in an attempt to cast aside his former restrictions and push his work in a new direction. Again it’s a development I might compare to that of Jean Giraud when he assumed the mantle of Moebius for his more controversial output, however while Giraud thrived under his new found freedom Kirby wasn’t so fortunate. Of his departure from Marvel Gold writes:

‘he withheld his most interesting ideas, and in 1970 took them (and himself) to rival publisher DC. There he launched New Gods, Forever People, and Mister Miracle, actually one incredibly complex saga that became known as the “Fourth World” (…) His characters were fantastically colorful, flawed, Shakespearean in their triumphs or dooms. Each plotline became not just a series of fight scenes but an allegory about Vietnam, religious fervor, poverty, the nature of aggression and evil. The panels got bigger again, and doublesplashes became a normal part of each issue. And yet it wasn’t popular. You had the sense as reader that you were grabbing on to a train thundering down a mountainside at a dangerous clip, the scenery a blur. In part, Kirby was learning about his dreamworlds as he wrote; in part it was hard to keep track of everything. None of the series lasted past eighteen issues. The remainder of his work is generally that of a man tired of having the rug yanked out from under him.’

(Gold, 2005, p262, 266)

While in recent decades this work has received more critical acclaim, even now it remains more or less eclipsed by his contributions to Marvel. All the same it’s nice to see his somewhat edgier side being represented by a portion of the exhibit; Jason Atomic’s ‘Non Submissive Female’ below embodies an aggressive image of the empowered woman while another series of Vlad Quigley prints show some of Kirby’s black characters dressed in provocative attire – it’s worth noting in this regard that his character Black Panther was comics’ first black superhero.

By his death in 1994 Jack Kirby may have been far from his highest point, but the legacy speaks for itself. Going full circle – back to the flyer image at the start – I’ll finish with two pieces of Kirby’s Devil Dinosaur (the original and the homage) and a particularly interesting final quote from Glen David Gold:

‘At age sixty, he was still producing art like the Devil Dinosaur doublesplash, which illustrates an ancient myth about a dragon that eats the moon. At a glance, it’s abstract, but, like his fantastic machinery, each element resolves into something entirely functional. Freud, who was onto myths like a hawk on field mice, suggested that myths were sacred because they were, by avenues not yet understood, public dreams. So sidestepping that “genius” epithet, here’s a title we might agree upon: Jack Kirby, public dreamer.’

(Gold, 2005, p266, 267)

Between the faceless comics ‘genius‘ I knew of before and the flawed ‘public dreamer’ I definitely know which I prefer.

Posted by Ozy

Posted by Ozy