Much as I did with Sin City (1991) I’ve made mention of Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso’s comic 100 Bullets more than once now in connection to my research and artwork, so it’s high time I did a proper write up on it in recognition of this. I’ve previously read several books in the series (of which there are 100 issues across 13 volumes) but for the sake of keeping things succinct and relevant here I will be focusing on the debut book First Shot, Last Call (2000) as a sample of its storytelling approach and style.

The story’s opening chapters centre around a simple but compelling premise: a man referring to himself only as ‘Agent Graves’ visits the victim of some grievous wrong doing and informs them who is responsible, giving them a briefcase containing supporting evidence, a pistol and 100 untraceable bullets along with immunity to any ensuing investigation – essentially a chance to have revenge and to get away with murder. It’s a setup which inherently challenges the characters’ morality and affirms its place as a neo-noir take of the bygone pulp genre.

What’s perhaps most clever about this basis though is its dual function. Considered in a standalone capacity this volume offers one-off stories of revenge centring around differing protagonists and reasons for retribution. Taken as part of a larger whole however there are enough clues towards an overarching plot to maintain readership for future instalments. It is thus that it captures the attentions of the casual reader in the short term while ensuring long term interest is retained to facilitate the series survival and success; the immediate emphatic appeal of downtrodden people given a chance to settle a wrong in their lives is counterbalanced by the mystery surrounding Graves and his ‘game’.

In this book for example, we are initially treated to the story of Dizzy Cordova; a former gang member mourning the shooting of her husband and child, freshly released from prison. The second character story meanwhile focuses on a bartender Lee Dolan; a man whose life was effectively destroyed by false charges of child pornography. Both these stories begin with Graves handing over the briefcase as a catalyst and yet both could be taken out of context and still function as satisfying pulp style shorts. It’s remarkable just how much they differ in execution and resolution too, with Dizzy getting her revenge and closure while Lee backing down results in bitter tragedy.

Graves and initial hints towards a sinister organisation ‘The Trust’ also serve as a running thread through these two narratives, maintaining a structure around the shorts while a coda chapter at the end alludes to the scale of ‘the game’ by linking a series of seemingly unconnected people – something which gives rise to one of 100 Bullets’ driving themes, that “everyone is connected” (p55).

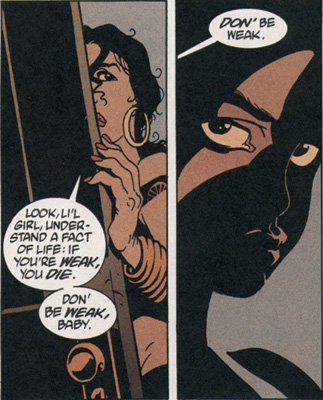

To the series’ credit, in spite of the fairly outlandish premise the situations often possess a high degree of realism most notably in terms of character behaviour and development. That so many of the cast are flawed and prone to immoral behaviour potentially makes it sound nihilistic, but it would be more accurate to say this roots the narratives in a tangible sense of reality with death seemingly a hairsbreadth away and sustained tension being used to maximum effect before each story’s climax. It’s a subjective point, but in my case at least the character faults drew my sympathy. The convincing use of accent and dialect in the speech adds a great deal too; it takes some getting used to but again enforces a sense of credibility while also creating a powerful sense of place within each narrative, being filled with the sort of language you might very well hear around the real location.

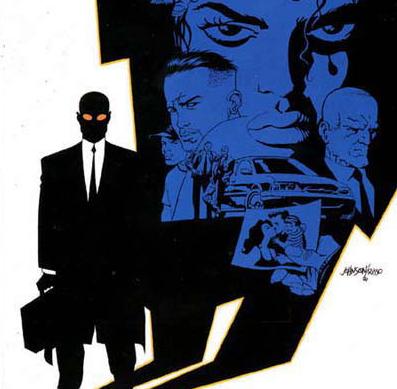

Considering Risso’s art 100 Bullets perhaps isn’t obviously impressive. Viewed in the wrong light its drawings might be considered overly simplistic and half finished. What ultimately betrays the skill with which they are made though is the realisation that they are not simple for the sake of cutting corners, rather they are economical to enforce an image on the reader that is both powerful and memorable. Similar to (perhaps directly inspired by) Frank Miller’s Sin City the style appropriately pays homage to the high contrast depictions of film noir with large areas of shadow obscuring characters and backgrounds, while including surreal touches of illumination such as the teeth and eyes. These compositions and their capture of form are incredibly effective, managing to convey atmospheric scenes without resorting to slavish amounts of detail.

As I’ve formerly mentioned in other writing, the colour palette does an outstanding job of complimenting these stark depictions too: a specific scheme being used for each story giving them all a distinct visual flavour and tone, making it possible to differentiate them at a glance and once again keeping them memorable.

Dizzy’s portion of the book begins saturated in sun washed oranges and browns before giving way to greys and blues for the night storm at the end, something which connects with film noir’s tendency of gradually descending into night as the metaphorical ‘heart of darkness’ is reached. Lee’s story on the other hand is differentiated by deep reds and lurid yellow highlights, depicting the neon sleaze of his downtown bar job and frequent visits to an exotic dancer. It’s a method which gives the stories a distinct visual personality by reflecting some of the subject character and their situation in the colour scheme, emphasising the shift in perspective on an almost subconscious level.

It takes some adjustment but 100 Bullets is to my mind a defining example of modern comic book noir; staying true to the genre tropes of moral ambiguity, pervasive mystery and heavily stylised visuals while placing a modern and distinctly gritty twist on the formula. Like the artwork it never does more than it needs to, telling streamlined tales of greed and revenge with just enough intrigue to keep you reading.

Posted by Ozy

Posted by Ozy