Having talked a lot about embracing the noir influence on cyberpunk and connecting with some of the modernist values echoed in my own setting, it seems appropriate that I take a moment out from cyborgs and scribbling to have a specific look at the era’s fashions.

My intention has been to flavour rather than saturate the dress of my characters with the aforementioned style for fear of pushing too hard in a steam/retro-punk direction. However, thus far most of my references have been skimmed directly from film noir and other non-specific sources; an approach which has proved adequate but honestly slightly lazy, missing the finer details and a broader overall view. With crowds of Branch’s inhabitants likely to appear on the graphic’s forthcoming pages it seems more important than ever that I have unifying influence on their clothing and general style.

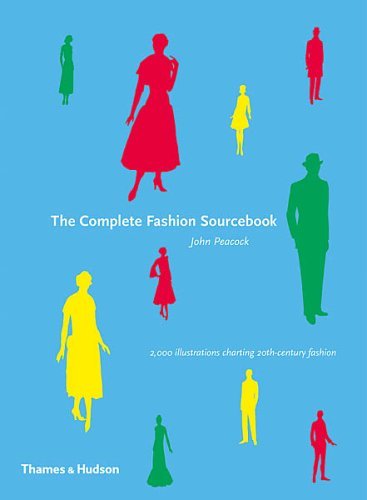

Following my recent module presentation in which I expressed this concern, a fellow student (thanks Lucy!) kindly lent me The Complete Fashion Sourcebook (2005) by John Peacock. Charting the development of fashion through the majority of the 20th century, the book predominantly uses illustration to show rather than tell which – given my own chosen medium – is quite fitting. It was particularly pleasing to find that the introductory write-up for the 1940’s section struck an immediate chord with my aims:

‘Women’s fashion in the 1940’s divides into two separate parts: from 1940 to 1946, and from early 1947 to the end of the decade. The first part was dominated by the Second World War. Dress, echoing military, was consciously and almost wholly utilitarian. In the United Kingdom, rationing came into effect in the summer of 1941 and the following year saw the introduction of the Utility Clothing Scheme which restricted among other things the amount of cloth that could be used in garments, the maximum length and width of a skirt, and the number of pleats, buttons and trimmings.’

(Peacock, 2005, p119)

‘Utilitarian’; a word I’ve formerly used in relation to my character designs. Indeed, with the ‘make do’ basis for my setting and general ‘used future’ vibe I have in mind it’s remarkable how well the rationing behind late WW2 clothing meshes with the context of my graphic. Being a time discouraging frivolity in design and a general less-is-more approach I feel it fits in with Branch’s inherent desperation and the largely closed economy of a space station.

Contrary to this I’d originally considered studying fashions of the 1940’s and 50’s, taking inspiration from throughout noir’s golden era but was made to reconsider as the text offers some interesting insight into the changing attitudes following the war:

‘Paris, traditionally the world’s most powerful force in fashion, lost much of its influence due to wartime isolation. But in 1947 it came back with a bang. On 12 February of that year the French couturier Christian Dior launched his ‘Corolle line’, instantly nicknamed ‘The New Look’ – the most famous and controversial collection any designer has ever produced (…) it was ultra-feminine and grandly extravagant, and arriving as it did so soon after the war, when some rationing and restrictions were still in force, it caused a sensation. The old pre-1947 lines were demolished at a stroke.’

(Peacock, 2005, p119)

With ‘The New Look’ moving away from the restrained designs of old into more luxurious territory the motivation behind late 40’s and 50’s fashion seems ill fitted to the context of the graphic while this clear divide suggests I’d benefit from an exclusive focus on WW2 wear.

As stated this is specifically considering female wear, with men’s fashion of the time being abruptly dismissed as ‘relatively stationary and somewhat dull, dominated as they were by military uniform’ (p120). It’s a harsh judgement perhaps but looking across the decade there are only slight variations on the typical suits and trench coats – this isn’t exactly problematic to me as it provides a more stable template to work from and use artistic licence with, while I confess that I know far less about women’s clothing during the decade anyway.

Moving on to the actual illustrations I’ve collected a small cross-section, specifically selecting the most eye-catching designs as potential inspirations – forgive the slight distortions, hardbacks can be a nightmare to scan:

Considering the female outfits from the above 1941 day wear page, there’s a notable focus on pulled in waists specifically the prominence of belts – likely a reflection of the times aforementioned military influence – while skirts are typically cut to knee level; saving fabric while remaining modest. Meanwhile the male garb here is a fairly typical three-piece suit with wide lapels, waistcoat beneath and requisite Trilby, not too dissimilar perhaps to my last design for Baby Face.

Moving away from formal wear I find it interesting that we see women’s leisure outfits sporting trousers alongside the skirts; a sign perhaps of the gender’s increased emancipation as the formerly male dominated jobs were offered to them during wartime. This time around the male example is slightly reminiscent of Baldo, the more elaborate collar and double-breasted pockets being something I may incorporate into my own design.

Moving on to the day wear of 1943 there’s a notable increase in the amount of fabric being used for both men and women, possibly as a result of the war approaching its end. The padded shoulders also appear to be more prominent while the military influence is especially strong in terms of the hat and coat designs.

Moving on to the day wear of 1943 there’s a notable increase in the amount of fabric being used for both men and women, possibly as a result of the war approaching its end. The padded shoulders also appear to be more prominent while the military influence is especially strong in terms of the hat and coat designs.

Finally, I grabbed this page of 1940’s evening wear just to throw in something a little different for my references. While Branch is intended to be rife with poverty there will be a select few who benefit from or even excel under the circumstances. Drawing upon designs such as the above could provide an interesting variation on the general style to keep things diverse, while emphasising difference in wealth on an immediate visual basis.

As the graphic progresses I should be returning to these pages on a regular basis for design ideas and general inspiration, though if I get the time I’d like to research a few more sources to ensure the aesthetic is soundly developed. At the very least the influence should feel more informed now.

Posted by Ozy

Posted by Ozy