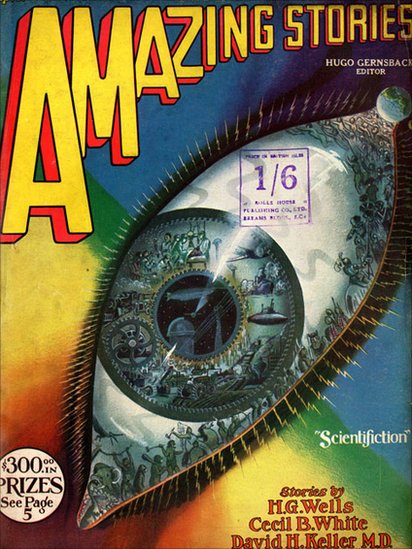

When I visited the British Library’s Out of this World exhibition last month, I happened to overhear a school teacher leading a class of young children around. Stopping in front of a poster not unlike the one above, she quizzed the pupils:

“What do you notice about the lady in this poster?”

“She’s being chased by an alien.”

“And what else about her? What about what she’s wearing?”

“She’s not wearing very much…”

While I doubt the inquisitive child grasped the implications of this point, the innocent observation sparked a line of thought for me which was seemingly answered in the form of BBC radio programme ‘Cat Women of the Moon’.

I may not have addressed gender directly in my research and writing and it’s not the focus of my comic, however I do believe the topic has indirect relevance all the same. Taking its title from the 1953 B-movie of the same name, Cat Women of the Moon considers gender, sex and the portrayal of women in science fiction, inviting an array of genre writers and theorists to consider what the kind of all female society featured in the film might signify about the real world and the motives of author and reader alike.

Ideally science fiction entertains with its escapist elements while addressing real world issues via their subtext; at the start of the programme prolific author Ian M Banks makes an optimistic statement of the genre’s advantages, stating that ‘In science fiction you can change human nature… you can question things like gender in a certain way and sexual roles and so-on.’ Specifically contemplating this topic Nicola Griffith – another respected contemporary SF author – also supports this point, saying:

‘There’s nothing science fiction writers and readers like better than to turn over the stones of cultural institutions and look at the assumptions wriggling underneath. So science fiction gets to ask of gender: what if our understanding of gender is wrong? What if it doesn’t have to be this way? What if we can change it? Science fiction basically can turn gender from a war or a life sentence or a prison, to a game or a fashion statement or even a rollercoaster ride.’

This freedom and opportunity to challenge established trends is undeniable, but taking an objective look at the genre’s history gender roles are as commonly affirmed or exaggerated as they are shaken up.

The motive behind the original ‘Cat Women’ was more likely fear of rising feminism and the challenging of male dominance than the championing of female empowerment; the titular characters presenting an exotic nemesis rather than sympathisable protagonists. The programmes presenter Sarah Hall – another renowned sci-fi author – points out that even established literary classics such as George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World suffer remarkably stunted views regarding women given their revolutionary tone. As she puts it:

‘In these books both the female leads Julia and Lenina seem trapped by conventional notions of the standard, slightly lesser female – even while the authors pushed valiantly against ideas of sexual conformity (…) are they failures on the part of the authors to blue sky think where female characters and female roles are concerned?’

Just as society itself has progressed in its gender views though, so has much of the genre’s writing. Nicola Griffith’s 1994 novel Ammonite might be seen as a more balanced modern equivalent of the ‘Cat Women’ scenario, something contrasted with the more regrettable tropes she attempt to transcend:

‘Women were either evil man haters, or they were rather dim or they were six-feet tall wise, kind vegetarian amazons which is what you got with the utopian feminist books of the 70’s and 80’s – or they were poor pathetic frightened creatures. I wanted to write a world with different cultures; it wouldn’t be a monoculture it would be different cultures where women would play all the roles. They would be smart and stupid, they would be traders and protectionists, they would be angry and relaxed. They would play everything, they would simply be people.’

Another author on the programme – Farah Mendlesohn – supports this point latching onto a similar issue in the genre’s portrayal of women:

‘women need to stop being women and start being people, when people think people they think MEN… Women are still the add on extra; in all children’ cartoons or in an awful lot of Hollywood movies they’ll be five men with lots of distinguishing characteristics and the woman; and the woman’s distinguishing characteristic is to be a woman (…) women are people and they have to start thinking of themselves as people.’

It would be nice to say that this sort of thing has died out in contemporary fiction, it’s definitely diminished in recent decades at least but I think it’s safe to say there’s still a fair amount of it drifting about in popular culture.

Take a film I saw recently for example; Zack Snyder’s Sucker Punch.

From a directorial or visual standpoint the film was highly accomplished and I felt there were interesting ideas involved, but as I heard one reviewer aptly put it there was a sense of dishonesty to the whole thing which I could never quite shake. It’s not the sort of barefaced misogyny we might of seen in the past, but the alleged intention to empower its female cast doesn’t withstand scrutiny.

With most of the story taking place in their minds, the question begs how credible the fantasy really is: Why the fetishised outfits? The predominant setting of a bordelo? The erotic dance routines? I left the cinema with an uncomfortable feeling the fantasy was more likely intended for a male demographic in search of action and sex appeal. Not exactly an outrageous intention by today’s standards but perhaps the fact it’s so readily accepted in mainstream cinema is the more disturbing point.

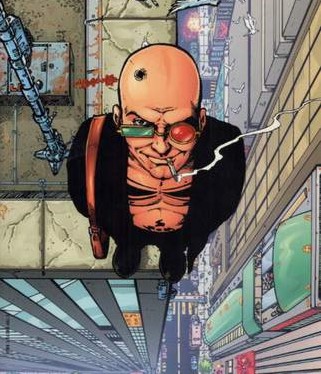

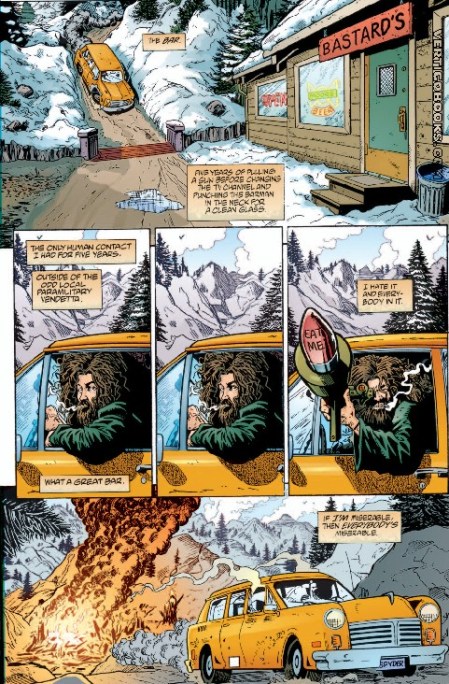

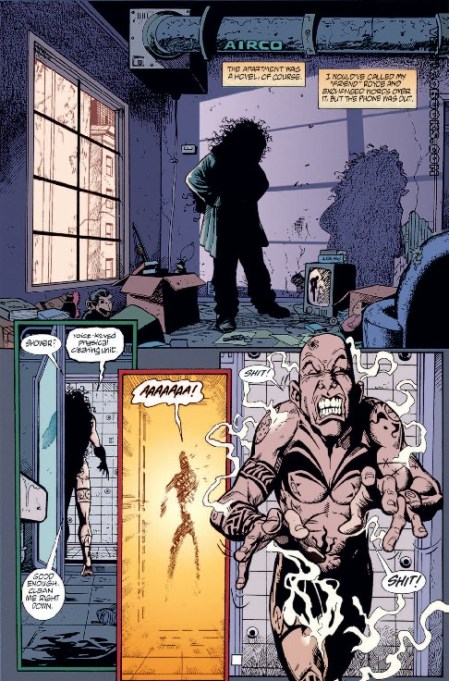

In my own work I think I made subconscious choices about characters’ gender and how they are portrayed, but I’ve neglected to give it any serious thought until now which seems like an oversight. ‘Scratch’ – a ‘tough’ cyborg detective figure and my main protagonist – ended up being a woman mostly as a way of ducking under unfortunate macho clichés so frequently bestowed on men, but also because I felt a female detective would be more interesting.

I find my self questioning this motive now: Why exactly should a female detective be more interesting? Because it’s a stereotypically male role? Because it’s abnormal? While on the surface I do want her to be an empowered character of distinct personality, part of me worries this could be inadvertent indulgence in a ‘tough woman‘ novelty – something I wish to avoid at all costs. The choice of gender and generally masculine appearance does have some grounding in the themes and setting at least. The use of the term ‘procedure’ in my script I felt likens the operation for cyborg enhancement to a sex change, in this sense supporting the idea of her gender identity being warped by the alterations.

There’s interesting territory to explore in this regard, but I need to be careful it’s to complement my subject matter rather than for flimsy personal reasons. As the quotes highlight, science fiction presents a nearly unparalleled freedom for reinvention of societal norms and altogether disregarding the matter of gender in my scenario would be a wasted opportunity.

At the very least, I promise there won’t be skimpy sailor uniforms any time soon…

Posted by Ozy

Posted by Ozy