Putting aside that Touch of Evil (1958) is a firm favourite of mine within the noir genre, it also makes for another fitting continuation to my roughly chronological progression of subject films. Not only does it seem to follow on from Strangers on a Train (1951) in terms of the genre’s rising focus on character driven narrative but it’s also considered by many to be one of the last examples of film noir’s golden era (expect spoilers).

Given the respected reputation it possesses today it’s hard to believe the film was a B-movie, but this may also of been what allowed boundaries to pushed; dabbling in even darker subject matter and muddier morality than its predecessors. Orson Welles – who both directed and co-starred in the picture – is said to have predominantly shot at night to minimise studio interference, only to have the film forcibly recut by Universal against his wishes. All in all, there’s a lot of confusion regarding the different versions (of which there are three), aspect ratio and intended narrative – hardly helped by my viewing from an ancient VHS copy – but as far as I can tell it’s the 108 minute alternate version from 1976 which I’ve watched.

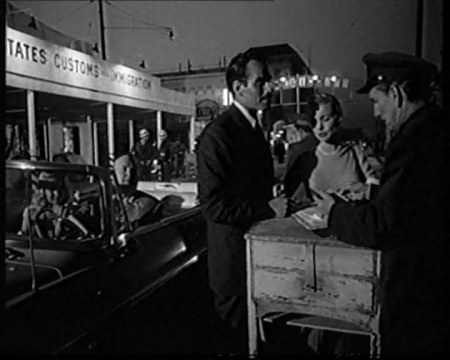

And what a movie it is. Opening with an extended crane shot tracking a car rigged with a bomb we are gripped from the first few seconds and sucked into a world of murder, corruption and deceit. I noted with my previous noir subjects that they typically begin during day light before later descending into the darkness as the climax approaches, however here by starting in darkness it’s as though the film acknowledges a darker tone and sense of foreboding within these opening minutes.

As the car in question explodes crossing the Mexico-US border, taking a powerful construction contractor with it the plot’s key players assemble at the scene of the crime: Miguel ‘Mike’ Vargas, an idealistic Mexican narcotics officer is torn away from his newlywed to investigate the bombing when American Police Captain Hank Quinlan (played by a heavily made up Welles) intervenes, aggressively taking charge of the matter.

For starters, the nationality of these two leading men introduces an uncomfortable element of racial tension to the proceedings. Though the choice of Charlton Heston made up as a Mexican for Vargas suggests pressure from Hollywood to ‘play it safe’, the handling of the racial undertones is far from immature or one sided. Quinlan’s intolerance is highlighted in his objections to Vargas speaking Spanish in his presence, while even Vargas’s American wife ‘Susan’ displays a tendency to racially stereotype, condescendingly referring to a gang youth as “Poncho”.

As we enter the day again and the two reluctantly cooperate in the interrogation of a Mexican suspect things take a critical turn when Quinlan claims to have discovered dynamite in the home of the accused. Identifying the box it was found within as an empty one he previously overturned, Vargas accuses Quinlan of framing their suspect marking a key change in direction for the narrative. To some extent both are detective figures attempting to solve the initial bombing, but as matters develop and the conflict between them escalates, their interests gradually shift from the crime itself over to smearing each other’s reputations. Soon it becomes clear that the bomb was merely a catalyst for something far more sinister.

As Vargas sets about searching for incriminating evidence of his opposite number’s corruption in the police records, Quinlan is approached by ‘Uncle’ Joe Grandi – local crime lord and target of the ongoing dope crackdown – with a mutually beneficial scheme to incriminate Susan in a drug scandal and ruin Vargas in the process, an offer which proves just too tempting. There’s never much doubt that Quinlan is the real villain of the piece and that Vargas is our hero, but at the same time Welles’s antagonist has a level of character complexity that isn’t often seen in the medium making things less clear cut than they might first seem. As villainous as he may initially appear with his abrasive manner, ruthless scheming and grotesque obesity it’s hard to find Quinlan entirely unsympathetic.

As matters begin to spiral out of control we hear more about him from Pete Menzies; his long time partner on the force; Depicting him as role model for his own career, Menzies enthusiastically tells Susan at one point how Quinlan got his “game leg” taking a bullet meant for him along with several other mentions of him overcoming alcoholism. Being treated to a glass of Bourbon by Grandi in spite of repeated claims that he no longer drinks, we witness the start of a steep decline that is ironically as likely to draw empathy from viewers as it does horror.

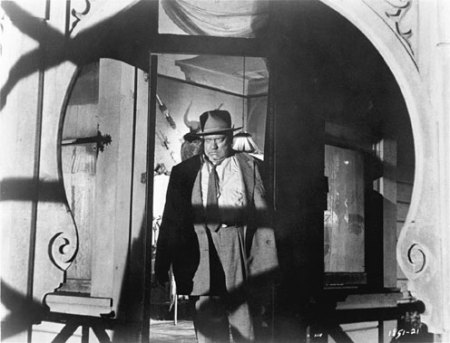

Alan Silver and James Ursini’s The Noir Style (1999) offers a particularly insightful take on how this duality is represented within the visuals in relation to the image above:

‘Bulk also adds vulnerability to Detective Hank Quinlan (Orson Welles) in Touch of Evil (1958). Quinlan is a man trapped by the web of violence and deceit he has woven around himself. While his massive figure seems about to explode from an excess of poisonous fluid springing from his corrupt nature, his face sags as he realizes his plans have back fired and he is now caught in his own web. The frame exhibits several layers of metaphorical traps. In the foreground he is framed by the arch of the porch with its curving designs resembling the jaws of a monstrous animal. Further within the shot the door frame acts as a tighter trap, enclosing his formidable figure. And finally, two shadows cut across his body, one horizontally over his midriff and one diagonally at his knees. These foreshadow his imminent doom. In the background Welles the director places a pair of horns, strategically positioned to give the impression that they are growing out of his head, a none too subtle demonic reference.’

(Silver, Ursini, 1999, p71)

Indeed; while the film embodies most of the crooked camera angles, heavy shadowing and symbolism which had become a genre standard by this point Touch of Evil has its own distinct look, perhaps thanks to the offbeat setting or Welles’s directorial eye resulting in striking often disturbing imagery which complements the story’s tone perfectly.

As night descends once again and Grandi’s gang forcibly intoxicates Susan, the shift back to a darker tone is once again emphasised as Quinlan takes things a step further. No longer content with a pinning a mere drug charge on his foe, consumed by alcohol and anger he strangles his accomplice in order to frame Vargas’s wife for murder – something which in turn echoes the alleged murder of Quinlan’s own spouse by the same method.

Again, this draws viewer sympathy alongside their disgust, but more disturbingly it also draws comparisons between our hero and antagonist with the suggestion that Quinlan may once have shared a similar outlook on law enforcement as his enemy – something lent further weight as Vargas descends into a bar brawl in search of his own missing wife. His fall isn’t so great certainly, but the parallel is definitely there; for all their differences Vargas and Quinlan have a worrying amount in common by the end of the film.

The finale is slightly reminiscent to that of The Third Man (1949) in the way that Menzies – finding irrefutable evidence of his partner’s corruption and murderous behaviour – is forced to confront his idol with lethal consequences. However, while Harry Lime was portrayed as an unrepentant villain, it’s hard not to feel sorry for Hank Quinlan in his dying moments. In what may well be the film’s most powerful moment, Quinlan hears the wire recording of him shooting Menzies in panic, forcing him to face up to what he’s done for the first time, and finally acknowledge his downfall.

All this would have made for a traditionally satisfying Hollywood ending seeing evil punished and bravery rewarded, however Welles makes a bold move by denying us this in the final moments of dialogue. Arriving on the scene following Quinlan’s death, the assistant district attorney explains how the original suspect has confessed to the bombing, that in spite of everything “Quinlan was right after all”. It’s a final twist which throws former conceptions of good and evil into uncertainty, making an already hazy depiction of morality into a mire.

This is perhaps the essence of what makes Touch of Evil such an admirable piece of enduring film; it presents compelling, complex characters casting aside the traditional ‘crime and solution’ formula in favour of a personal descent into chaos that leaves no one entirely blameless or clearly to blame for that matter. It’s a movie more concerned with where things go wrong rather than how they are solved, which seeks to overturn polarised notions of good and evil.

Who really has the ‘touch of evil’? Anyone who’s desperate enough it would seem.

Okay, it’s late and I seriously need to get some shut-eye so I’m afraid this will have to be quick.

Okay, it’s late and I seriously need to get some shut-eye so I’m afraid this will have to be quick.

Posted by Ozy

Posted by Ozy